Experimental Design Exploring Predictors of Prosocial Behavior

RESEARCH QUESTIONS

What causes us to behave altruistically? What causes us to feel compassion toward another human being, and then act on that feeling?

How do a) emotional state, b) personal values, c) empathy levels, and d) tendency to avoid negative affect influence prosocial behavior?

METHOD

1) Utilized a survey with established psychometric scales to measure predictor variables

2) Developed a set of hypothetical scenarios based on a real-world cross-cultural study (Levine et al., 2001) and the World Giving Index (Low, 2015). The scenarios included a mix of helping individuals vs. groups, donating time vs. money, and more pleasant vs. unpleasant scenarios.

3) 42 Santa Clara University students took the survey which was analyzed using regression analysis

Example scenario: Imagine you are going for a walk on a busy street on a Sunday afternoon, and you don’t have anywhere else to be. You walk past some volunteers for a non-profit organization called HomeSmart that hosts programs for homeless people in the city.

The group is asking for money donations. (Money Condition)

The group is asking for volunteers for the soup kitchen. (Time Condition)

KEY CHALLENGE

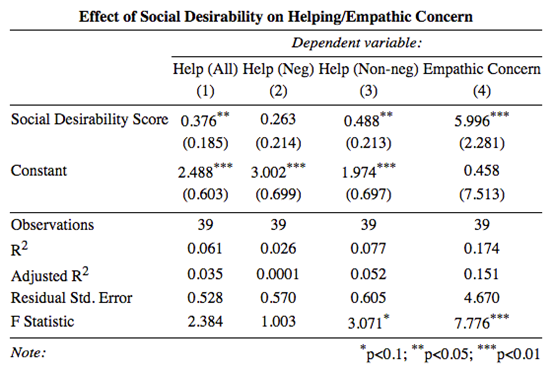

The best way to evaluate prosocial behavior is to provide participants with real-life opportunities to help without them realizing their behavior was part of the study. However, we were limited in our resources with this project in that we could only run an experiment online, through a survey. Therefore, we reviewed studies that explored prosocial behavior through real-world opportunities, and then crafted up hypothetical scenarios that participants could envision and to which they could answer virtually. This posed a major challenge, as people tend to inflate their predicted or hypothetical behavior with regards to altruism. However, to adjust for this bias, we included a Social Desirability Scale (Crowne & Marlowe, 1960) to statistically account for their responses to virtual behavior. The regression table below reflects that including this scale was effective, as it was a significant predictor of decisions to help and empathic concern.

RESULTS

The study found evidence of three main effects:

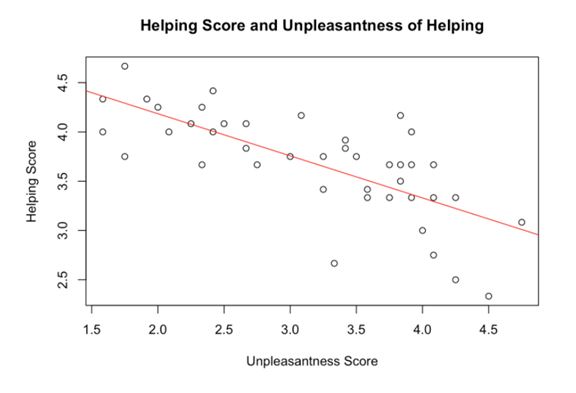

The more a scenario is perceived as unpleasant, the less likely the participant is to help in that scenario.

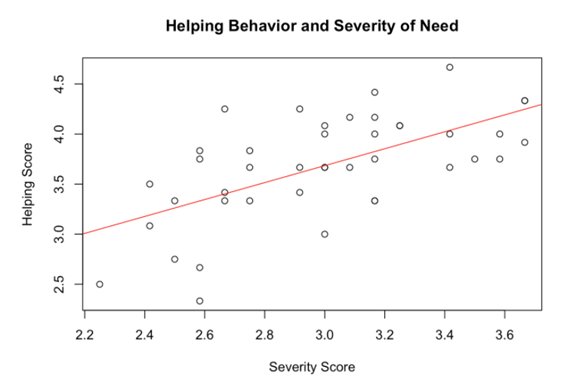

The more severely a person or group is perceived as needing help, the more likely the participant is to help in that scenario.

Of the four subscales of empathy (fantasy, personal distress, perspective taking, and empathic concern), empathic concern is the strongest predictor of whether a participant will help in a given scenario.

This study showed that higher levels of perceived severity of the person or group in need lead to higher levels of helping behavior. It also found that higher scores of unpleasantness of helping a person or individual lead to lower likelihoods of helping. Both of these scores make intuitive sense. People want to help those who need it the most, and based on the concept of avoided negative affect, people do not want to help if it means being exposed to an extremely unpleasant situation.

However, the more intriguing association here is that higher scores of severity are associated with lower scores of unpleasantness. This appears to contradict the concept of avoided negative affect, because assuming that those who need help more severely are in more negative situations, it doesn’t make sense that higher levels of severity are associated with lower scores of unpleasantness of helping. One possibility to explain this phenomenon may be that the participants are operating on that “feel-good” emotion one receives after helping someone who desperately needs it. Another possibility is that perceived severity scores have little to do with intended negativity of each scenario. Based on previous measures of Cronbach’s alpha that look at consistency of severity scores within each group of negative and non-negative scenarios, we find that this is actually the case.

IMPACT

This study continues the investigation into the role of prosocial behavior in our lives, and the reasons why human beings behave in prosocial ways, despite the costs to the self. To foster a more compassionate community and world, it is important to understand what factors contribute to people supporting each other more. Help and prosocial behavior tend to have ripple effects, so the more that our society can encourage deeper connections with each other and more helping behavior, the more that effect will grow in magnitude.